Like our planet’s resources, human resources are not infinite. They are not even abundant. In fact, good talent is becoming less abundant all the time. In the wake of the Great Recession, employees are bummed out, burned out and stressed out. While asking them to do more with less may have constituted a survival strategy over the past several years, it is neither sustainable nor in the organization’s best interest in the long run.

As the economy improves, employees are no longer happy just to have a job. Employers who fail to recognize that times have changed face losing their top talent to more agile employers who understand that without great people, people who are engaged in their work and eager to go the extra mile, there is no sustainable business model. Innovation ceases. The pipeline vanishes. Customers go elsewhere. And stock performance tumbles.

These are no ordinary times. Even before the recession, organizations across the globe were wringing their collective hands over looming talent shortages. In spite of relatively high unemployment, the fundamentals that predicted tight labor markets in the near future have not changed. Most agree that there is not sufficient talent in the pipeline to replace retiring Boomers. A widening skills gap is making it difficult for organizations to fill key roles. And a combination of talent-hungry emerging economies and increased globalization are escalating the war for talent.

PwC’s 2014 Global Talent Survey found 63% of CEOs are concerned about the availability of key skills.1

Top talent is not only becoming harder to recruit, it is also getting harder to retain.

A study by LinkedIn found that 85% of the global workforce is actively or passively looking for a new employer.2

At the same time, worldwide employee engagement levels are staggeringly low.

According to Gallup, more than 60% of the workforce is “not engaged.” They may be doing their job, but they are not inclined to give anything extra. Even worse, another 24% are “actively disengaged”—something Gallup defines as either wandering around in a fog, or actively undermining co-workers’ success.3

Figure 1. Based on research by PwC, LinkedIn, and Gallup, the days of employees being happy just to have a job are over. Employers that want to attract and retain the best and the brightest will need to fight for talent in the years ahead.

It’s About People

People cost far more than buildings. And they are far more valuable. They, not the machines they operate, the desks they occupy or the technology they use, are what ultimately creates shareholder value. Sadly, much of what has been called “workplace strategy” in recent years has been more about cutting costs than supporting people, frequently to the detriment of the latter. Research shows that happy, healthy and engaged employees produce more and cost less.

An organization’s workplaces, work processes and work practices comprise an ecosystem that has the potential to enhance employee well-being and thus, organizational performance.

Figure 2. According to the 2014 Willis Health and Productivity Survey, despite the positive benefits on business outcomes, few organizations currently make the investment in wellness and well-being programs.

Employee Well-Being and Organizational Outcomes are Intertwined

Many employers would assert they make a significant investment in employee health. But few do so in a way the World Health Organization and others consider optimal.

Since 1948 the World Health Organization has defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”4

If we know that good health requires more than just physical wellness and that employee well-being can have a big impact on business outcomes, why do so few organizations make the investment in it?

Only 11% of U.S. organizations offer what is considered to be a comprehensive wellness program.5

Among those organizations that have a defined budget for wellness programs, only 17% spend more than $150 per employee per year on their programs.6

Those that do are reaping the benefits in terms of increased engagement, greater productivity, reduced costs, greater shareholder value and more.

A Holistic Approach to Workplace Well-Being

Corporate wellness initiatives were first explored in earnest in the 1970’s and expanded in the 1980’s when risk managers began to understand the importance of ergonomics in workplace safety and employee health. As technology assumed a larger role in business, the study of “cognitive ergonomics” added mental workload, the man/machine interface and decision processes to the focus.

Only recently have organizations begun to consider what a 2011 Knoll report labeled “Holistic Ergonomics,” a concept that embodies the physical, mental, and social aspects of work.7

“…there is a disconnect between the limited breadth of issues that office ergonomics currently addresses, and the broader direction in which office work is evolving. If we focus on only a fractional part of office work (individual discomfort and posture during interaction with a computer), we risk missing many opportunities to enhance the well-being and performance of office workers.”

Thanks to a growing understanding of the importance of employee well-being, the concept is finally making its way into C-Suite conversations.

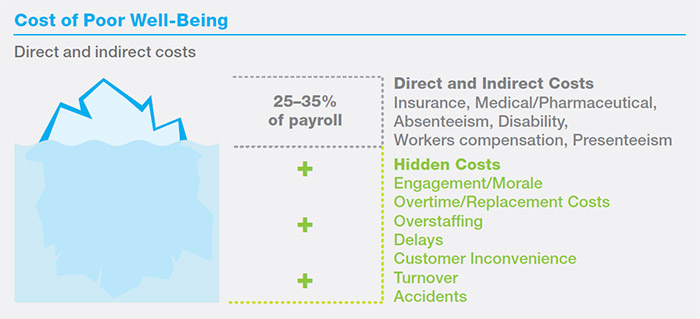

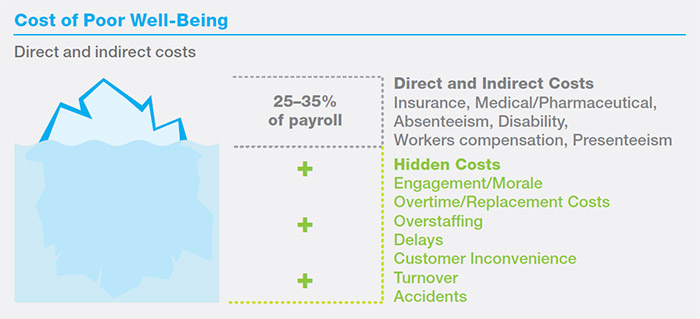

The Cost of Poor Well-Being

The direct cost of poor health is estimated at about 15% of payroll.8 But the cost of presenteeism—being physically on the job but not performing due to poor well-being— actually costs organizations even more than absenteeism.9 Taken together, direct healthcare and the cost of productivity lost to presenteeism can total between 25% and 35% of wages.10 But even that is not the total cost of poor employee well-being (see Figure 3).

Poor employee well-being can reduce engagement and morale, increase overtime, require overstaffing, increase turnover and make people more prone to accidents. Even something as simple as the shift to Daylight Savings Time has been shown to increase the incidence of heart attacks, traffic accidents, workplace incidents and presenteeism.11

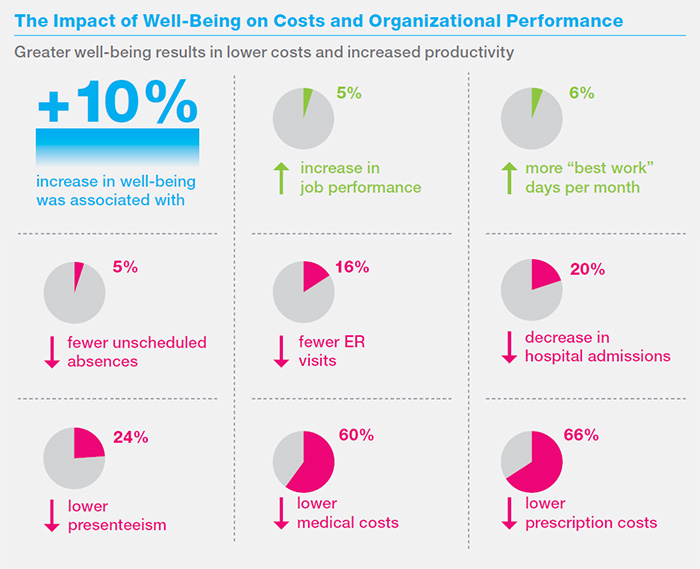

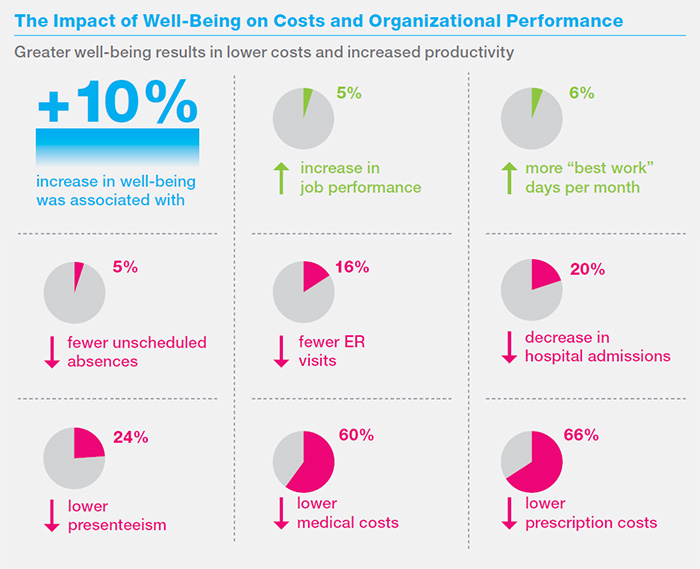

Employees with high levels of well-being not only cost their employers less, they are more productive and more engaged in their work as well (see Figure 4).12, 13

Eight different studies by organizations including Harvard Business Review, World Economic Forum and the American Journal of Health Promotion, showed a return on investment of wellness programs of between 144% and 3,000%.

Figure 3. Research from Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) and others suggest that the total direct and indirect cost of poor employee well-being can total 25% to 35% of payroll, but even that is just the tip of the iceberg.

Figure 4. According to research by The Healthways Center of Health Research, as well-being increases, direct and indirect wellness costs decrease and employee performance improves.4

What is Driving Corporate Well-Being Initiatives?

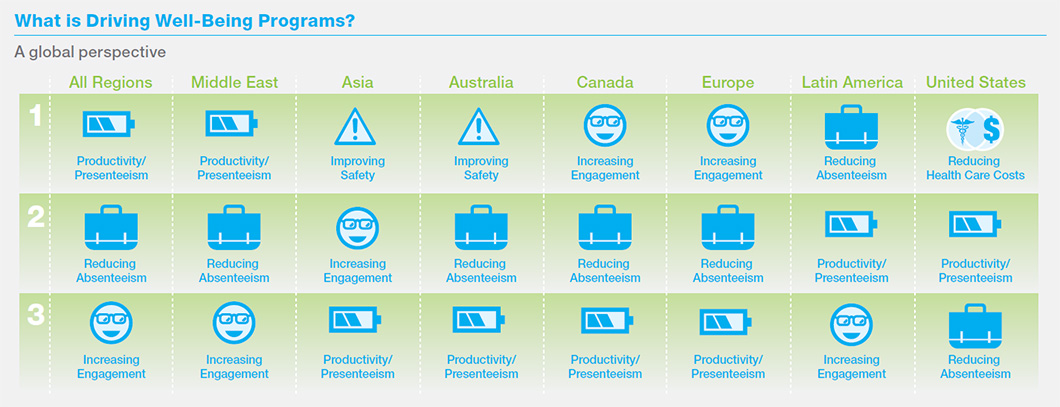

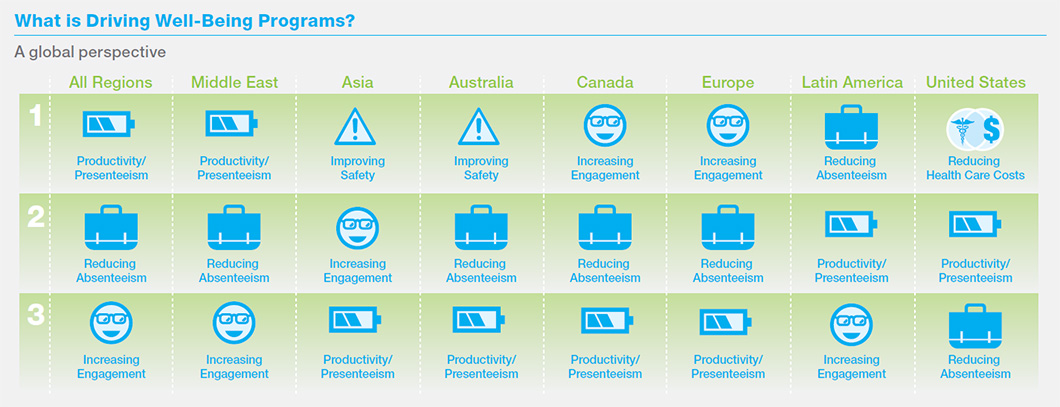

While cost reduction is the primary driver of well-being programs in the United States— due to the fact that domestic companies foot the bill for a large portion of employee healthcare—outside of the U.S., the three top drivers are reducing presenteeism, reducing absenteeism and increasing engagement (see Figure 6).15

Figure 6. Top drivers of well-being program across the globe based on Buck Consultants’ (a Xerox company) survey of over 1,000 companies in 37 countries.

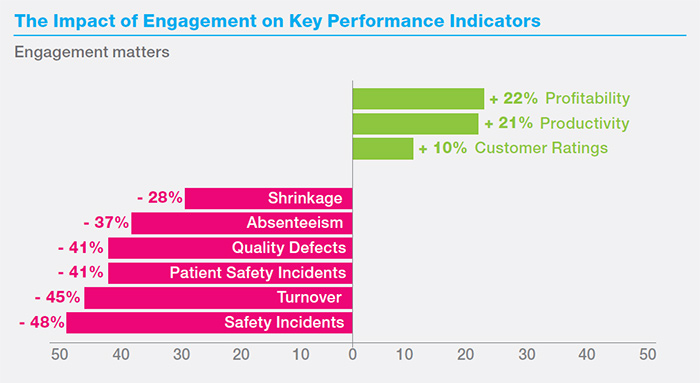

The good news is that increased employee engagement can significantly aid in improving the other drivers.

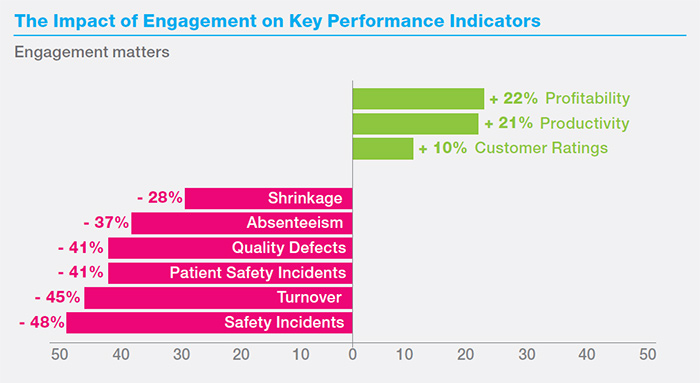

A meta-analysis of more than 250 research studies, covering nearly 200 organizations in virtually 50 industries across the globe, showed that employees with the highest levels of engagement are absent 37% fewer days than those with the lowest levels of engagement. What’s more, they are more loyal and more productive. The combined impact of these and other key performance indicators ultimately results in happier customers and a stronger bottom line (see Figure 5).

“Without a healthy workforce with the right skills and good working environment, optimal production isn’t achieved and reputational risks are exposed. Quality suffers. Turnover, absenteeism, and recruitment costs soar, and workers’ health and safety are jeopardized.”

—PWC 17TH ANNUAL GLOBAL CEO SURVEY

Figure 5. Based on Gallup’s meta-analysis of more than 250 research studies studies, covering nearly 200 organizations in virtually 50 industries across the globe.

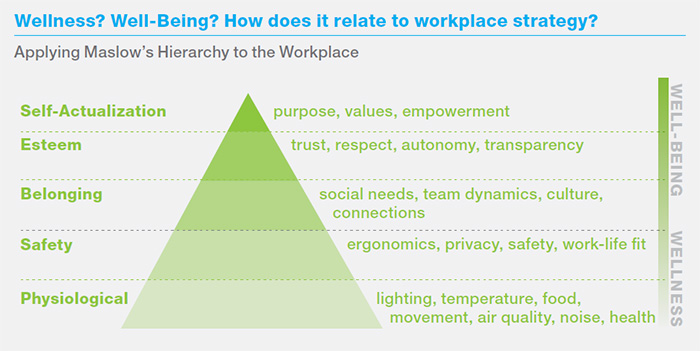

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

-

Self-Actualization: Purpose and meaning

-

Esteem: Self-worth and respect

-

Belonging: Relationships and connections

-

Safety: Security, safety and stability

-

Physiological: Physical health and comforts

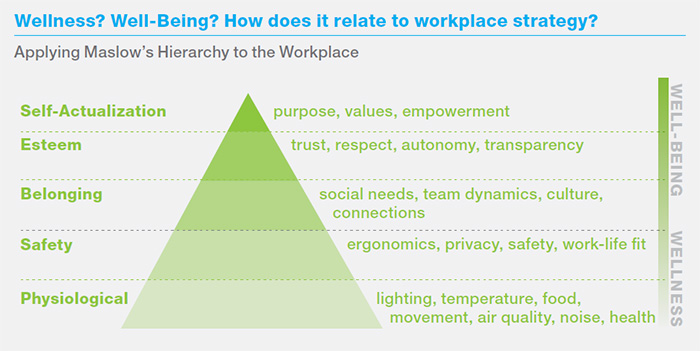

Figure 7. Only once an employee’s basic physiological and safety needs are met can they begin to think about the kinds of things that foster engagement.

The Role of Workplace Strategy in Employee Well-Being

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a useful framework for thinking about workplaces, work processes and work practices that can impact employee well-being (see Figure 7).15

In this framework, an employee’s physiological and safety needs serve as the foundation of the well-being pyramid. They are primarily related to the physical aspects of work and wellness: adequate lighting, thermal comfort, reasonable noise levels, sufficient privacy, etc. Employees are often dissatisfied when these basic needs are not met. But just as with Maslow’s original hierarchy, having them met, or exceeded, does not create satisfaction.

As one facility executive stated during a recent Knoll roundtable,16 “A great workplace is about more than real-estate. It’s about empowering people and making them feel connected to the company—to our brand and culture.”

Unless an employee’s basic needs are met, well-being—and not-so-coincidentally, engagement—is unattainable.

Ready, Set, Well

A handful of organizations have taken bold steps toward creating workplaces, work processes and work practices that promote the physical, mental and social health of its employees. Of the more leading edge solutions currently employed, Delos and CBRE recently partnered to create the first WELL Certified™ building (see sidebar, page 4).

There is no lack of resources when it comes to making health and well-being an organizational priority. In addition to Delos, Gallup, Healthways, Mercer, Towers Watson, Virgin and many others have been in the business of employee wellness.

Starting on the Path to Well-Being (see sidebar) and Putting Well-Being to Work (see Table 1, page 6) offer a process and a collection of practical activities from Knoll, and others, on how well-being can be easily integrated into an organization’s workplaces, work practices and work processes.

Closing Thoughts

Unlike other business assets—buildings, technology, investments—people have a choice about whom they work for, how much they give to their job and how they impact the people around them.

In the industrial era, people were needed to run the machines that created the things that led to business success. In a knowledge economy, human capital is the means to business success. The knowledge, skills, creativity and connections of its people are an organization’s primary, and oftentimes only, performing assets.

That changes everything. It changes the nature of competition. It changes the employer-employee contract. It changes the perspective of the value proposition from that of the pursuer to that of the pursued. It dictates that the retention of talent and attraction of the best and brightest take precedence over short-term interest. It changes how employers need to treat their people—addressing their higher needs and wants if they wish to keep them on board. And it changes how organizations think about the where, when and how of work.

Ultimately, what is good for people is good for the organization. To win in the years ahead, organizations will need to concentrate efforts on ensuring the sustainability of their most important asset, their people.

Putting Well-Being to Work

Table 1. Offers a collection of practical activities on how well-being can be easily integrated into an organization’s workplaces, work practices and work processes. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs creates a framework for these activities. Physiological and safety, the most fundamental levels of needs, form the foundation of the pyramid, while belonging, esteem and self-actualization shape the top.

Workplaces

Offer connections to nature

-

Design for visual access to daylight and outdoors

-

Incorporate plants throughout the workplace

Ensure physical comfort

-

Use sound masking or sound absorbing materials

-

Provide refuge rooms for retreat and concentration

Encourage movement and activity

-

Centralize printers, trash cans and other commonly used resources

-

Provide a variety of fitness options on- and off-site

-

Beautify stairwells

-

Provide a range of work surface heights

-

Create spaces to accommodate standing meetings

Work Practices and Work Processes

Promote a healthy lifestyle

-

Offer healthy food and drink options on-site

-

Post and email healthy workplace tips

-

Provide wellness incentives

-

Establish work policies that discourage overworking

-

Encourage leaders to lead by example

-

Conduct wellness and well-being training

-

Offer medical benefits that include prevention

Encourage active workdays

-

Remind employees to take frequent breaks

-

Discourage working lunches

-

Promote standing and walking meetings

Workplaces

Provide holistic ergonomics support

-

Select seating that promotes a full range of movement

-

Provide monitor arms to reduce eye and neck strain

-

Offer keyboard trays to lessen muscle strain

-

Provide LED task lights to ease eye strain

Eliminate dangers and toxins

-

Equip indoor and outdoor areas with appropriate light levels

-

Ensure proper signage and wayfinding systems

-

Use low volatile organic compound (VOC) materials

-

Use non-toxic, hypoallergenic cleaners

Design for personal and information security

-

Install key-card access systems

-

Provide access to lockable storage

-

Secure electronic devices from cyber threats

Work Practices and Work Processes

Cover the basics

-

Provide workspace safety and ergonomics training

-

Provide workplace behavior and conflict coaching

-

Discourage and address office politics

-

Establish governance that ensures fair and equitable treatment

Reduce work-life conflict

-

Offer alternative work locations

-

Provide paid sick leave and personal time off

-

Discourage employees from coming to work sick

-

Support parental leave and eldercare

-

Offer flexible work schedules

-

Make counseling available

Create a culture of safety

-

Make it safe for employees to report threats

-

Establish clear workplace safety policies and procedures

-

Routinely hold safety awareness events

-

Develop a crisis communication plan

-

Practice for emergencies

Workplaces

Make it easy for people to connect with each other

-

Provide collaboration and communication tools to engage

on-site and remote employees

-

Plan on-site touchdown spaces for mobile employees

-

Offer technical support for on-site and remote employees

Foster community

-

Provide a “welcome” concierge

-

Provision gathering spaces with comfortable furnishings

-

Offer a café to promote chance encounters

-

Provide movable whiteboards to support informal meetings

Tell your story

-

Use physical environment to display brand and culture

-

Reinforce brand image throughout online presence

-

Provide storage and surfaces for publicly displaying personal objects

Work Practices and Work Processes

Create a sense of community

-

Recognize team accomplishments

-

Encourage mutual trust and respect

Promote inclusion

-

Provide diversity training

-

Include remote workers in activities

-

Respect time zone differences

Establish the vision

-

Ensure employees understand the organizational mission

-

Connect individual goals to the broader vision

-

Conduct regular performance reviews

Workplaces

Design spaces to build rapport and trust

-

Include employees in the workplace design process

-

Provide refuge spaces for one-on-one coaching

-

Incorporate glass walls to reinforce transparency

-

Incorporate enclave spaces for small group interaction

Provide for a range of sensory experiences

-

Use color, texture, materials, lighting and graphics to engage senses

-

Organize the spatial layout into different work zones

Work Practices and Work Processes

Provide opportunities for personal growth

-

Make career development a priority

-

Provide continual skills training

-

Offer tuition reimbursement

-

Fit the right people to the right job

-

Support cross-functional mentorship

Endorse transparency

-

Manage with integrity and consistency

-

Make it safe for employees to express concerns

-

Foster a “do the right thing” mindset

Gather and embrace feedback

-

Administer well-being and engagement surveys

-

Implement a 360-degree feedback process

Workplaces

Provide the power of choice and autonomy

-

Offer an array of workspace types to choose from

-

Provide furnishings and accessories that allow for personalization

-

Support consumerization of workspaces and technology

-

Provide easy-to-use, best-in-class technology

-

Eliminate entitlement-based provisioning

Work Practices and Work Processes

Embrace a higher purpose

-

Incorporate social good in organization’s mission

-

Eliminate hierarchy

Energize the workforce

-

Encourage and support volunteer work, community involvement and altruism

-

Offer sabbaticals, job swaps, career diversion and stretch projects

About the Author

Kate Lister is president of Global Workplace Analytics (GWA), a consulting and research firm that specializes in helping organizations and communities create and communicate the people-planet-profit business case for agile workplace initiatives such as mobile work, telework, flexible work, activity-based work, wellness and well-being programs and more.

Kate is the author of three business books all published by John Wiley & Sons. Her organization’s research has been cited by hundreds of media outlets including the Harvard Business Review, Wall Street Journal and Washington Post. She is a frequent speaker at live and virtual events.

Suggested Reading

International Well Building Institute—Promoting health and well-being in the built environment (2014)

The Willis Health and Productivity Survey Report 2014, Willis North America

The State of the Global Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders Worldwide (2013), Gallup

The Science of Well-Being (2011), Healthways

Holistic Ergonomics for the Evolving Nature of Work (2011), Knoll

Adaptable by Design: Shaping the Work Experience (2012), Knoll

References

1. PwC 17th Annual Global CEO Survey, PwC, 2014

2. Talent Trends 2014, LinkedIn

3. State of the Global Workforce, Gallup, 2013

4. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948.

5. The Willis Health and Productivity Survey 2014, Willis North America, Inc.

6. The Willis Health and Productivity Survey 2014, Willis North America, Inc.

7. Holistic Ergonomics for the Evolving Nature of Work, Knoll, 2011

8. National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans, Mercer, 2007

9. Promoting Employee Well-Being: Wellness Strategies to Improve Health, Performance, and the Bottom Line, Society for Human Resource Management, undated – estimate 2011

10. Calculated based on Society for Human Resource Management’s (SHRM) estimate of relative presenteeism costs

11. Daylight savings brings risks with loss of sleep, USA Today, March 7, 2014

12. The Science of Well-Being, The Healthways Center for Health Research, 2011

13. Evaluation of the Relationship Between Individual Well-Being and Future Health Care Utilization and Costs, Population Health Management, 2012

14. Working Well: What’s next for wellness? Buck Consultants, a Xerox company, 2012

15. State of the Global Workforce, Gallup, 2013

16. Technology Community Exploratory Forum, San Francisco, CA, 20-21 March 2014, Knoll

Download "What's Good For People?" to read the full paper