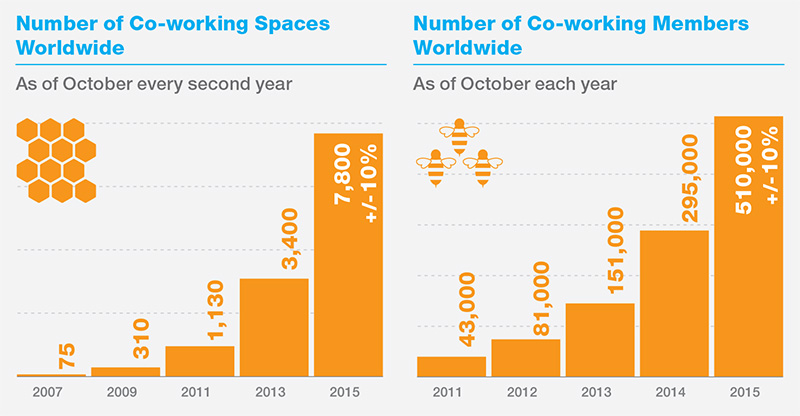

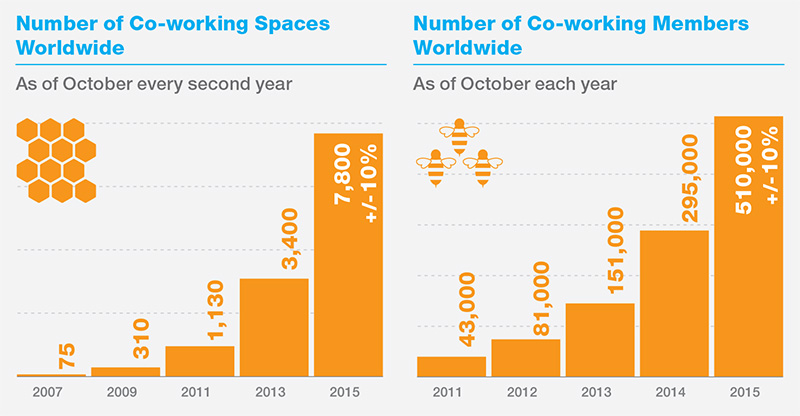

As one of the fastest-growing workplace movements of the last decade, co-working enables people from diverse backgrounds to work together in a common space. The number of co-working spaces around the world has increased by nearly 700 per cent since 2011. Globally, an estimated half a million people work in more than 7,800 shared workspaces today (Figure 1),1 a number which is expected to climb to 37,000 over the next two years.2 The rapid expansion of co-working has transcended its origins as an alternative to traditional office space, originally favoured by technology, start-up and freelancing communities. Today, a broad range of businesses — ranging from technology and professional service firms to consumer product companies — form a growing ecosystem that recognises the value of flexibility, community and shared resources. Businesses of all sizes and types — ranging from small start-ups to global enterprises — choose to locate employees or teams in shared work environments, either temporarily or on an ongoing basis.

Figure 1. Worldwide, the number of co-working spaces and co-working members has risen dramatically over the last decade.

Organisations have adopted co-working in a variety of ways, adapting the style to suit their particular needs. In some cases, companies are encouraging their remote or work-fromhome employees to join co-working spaces to reap the benefits reported by independent co-workers. These benefits include enhanced collaboration, productivity and job satisfaction. Other companies have launched satellite offices or incubators at existing co-working spaces, enabling employees to collaborate with outside partners, researchers and customers on a consistent basis. Such shared office environments allow companies the flexibility to devote dedicated space to facilitate these activities on an as-needed basis, without the stringent terms of a typical 10-year commercial lease. Co-working also enables organisations to provide the additional amenities and built-in flexibility which are increasingly essential to attracting and retaining talent in today’s competitive marketplace.

Organisations are finding that co-working can be part of an effective business strategy in other ways as well. For businesses with an underutilised real estate portfolio, co-working can create an extra revenue stream in these otherwise unused pockets of space. The average cost of unused space in the USA is US$25 per square foot or more, according to the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) 2015 Office Experience Exchange Report.3 By leasing vacant office space to current vendors, subcontractors and business partners with whom they collaborate regularly, companies can maximise business efficiency while monetising these valuable real estate assets. Although co-working spaces can be more expensive than traditional office space on a per-square-foot or per-squaremetre basis, they can provide corporate real estate (CRE) professionals with more flexibility when accommodating organisational shifts and expansions as well as when exploring new ways to support specialised teams.

This paper explores the following themes:

-

the inception and expansion of the coworking movement;

-

influences driving the continued evolution of co-working spaces;

-

how co-working best practices are applied to corporate work environments;

-

why co-working should matter to CRE professionals

The Evolution of Co-working

The global co-working movement can trace its origins to the emergence of ‘hackerspaces’ in the mid-1990s. These open workplaces provided physical spaces where people with common digital technology interests could gather to work on projects while sharing ideas, equipment and knowledge. Brian DeKoven, a game designer, coined the term ‘co-working’ in 1999, identifying a working style to facilitate collaboration and meetings. DeKoven’s goal was to introduce a noncompetitive process that would foster greater collaboration and support among traditionally isolated and hierarchical businesses.4 A few years later, a broader concept of coworking emerged with the 2005 launch of the first official collaborative workspace: the San Francisco Coworking Space, located in the city’s Mission District. The brainchild of computer programmer Brad Neuberg, this non-profit cooperative offered an alternative work community which combined the freedom and flexibility of independent working with the structure and community of traditional offices. By 2008, there were 75 co-working spaces in operation across North America and Europe. By 2011, the movement had expanded into Asia, gaining significant popularity in Mumbai, Singapore, Hong Kong and other cities with limited office space and rapidly growing start-up communities. Co-working also took root on the African continent, particularly in South Africa.

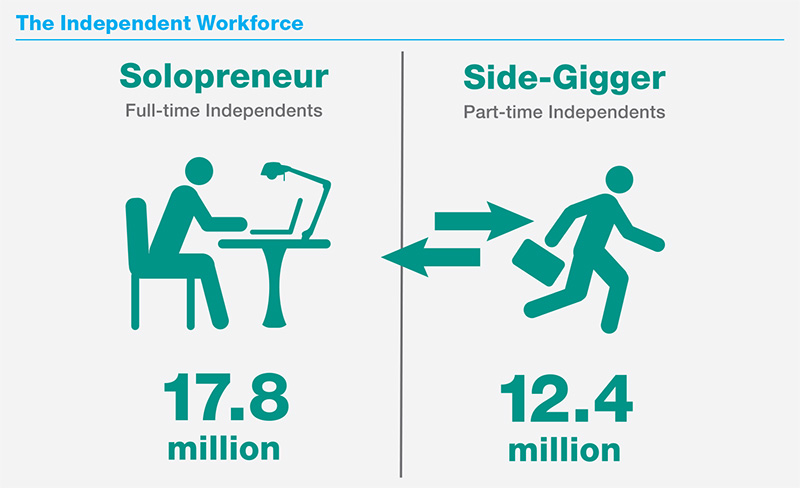

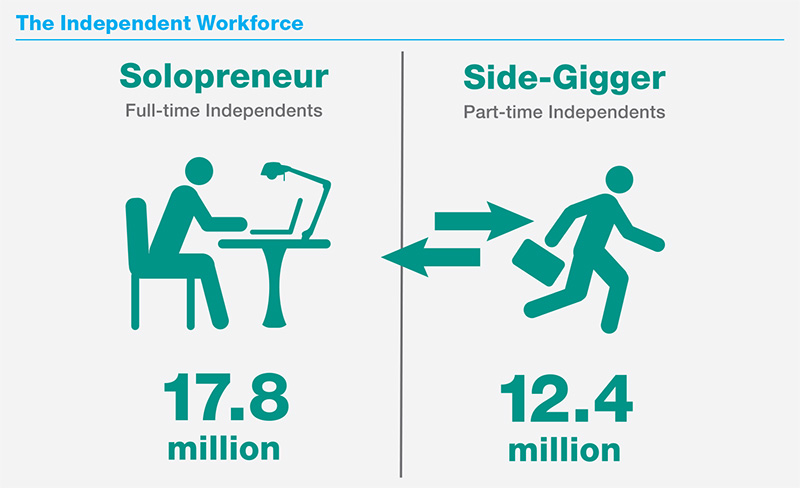

Figure 2. According to MBO Partners’ annual ‘State of Independence in America’ report, 17.8 million people are now full-time independent workers; in addition to the full-time independents, another 12.4 million ‘side-giggers’ take on part-time independent work.

The co-working movement continues to experience rapid growth. The number of shared workspaces nearly doubles each year and serves an increasingly broad community of users worldwide, including 30.2 million independent workers currently employed in the USA (Figure 2).5 Helping to drive this expansion is the growing class of entrepreneurs who work as sole practitioners in their own business ventures — known as ‘solopreneurs’ — as well as those who take on part-time independent assignments — sometimes referred to as ‘side-giggers’. Colleges, universities and other learning institutions are an important part of this evolution. Through the creation of on-campus ‘makerspaces’, students across all disciplines are increasingly introduced to collaborative, hands-on learning environments where they can discover and explore ideas more organically than in a traditional classroom. Typically housed in unused libraries, classrooms or storage areas, these spaces continue to expand beyond their engineeringschool origins.

As co-working continues its mainstream expansion, the movement is also extending its reach from primarily urban areas to less populated locations, as well as taking place in non-traditional venues such as hotels, abandoned warehouses and former churches. This rapid growth has spawned the creation of a new class of officesharing business venture. Perhaps the most prominent and ambitious example is WeWork, the New York-based business that currently serves more than 50,000 members at 77 locations across North America and Europe. Since its founding in 2010, WeWork has raised US$1.43bn and its valuation has soared to US$16bn, which positions the company as the world’s sixth-mostvaluable private company, making it nearly as valuable as the largest publicly traded office real estate company, Boston Properties.6

WeWork continues to attract an increasingly diverse tenant mix — ranging from General Electric to pharmaceutical giant Merck to the Guardian news publication. Companies have tended to place primarily research and development (R&D) and innovation teams and, to a lesser extent, human resources (HR) associates in co-working spaces. Many of WeWork’s business members are also choosing to use the space for employees whose organisational roles fall outside the realm of those traditionally associated with coworking spaces. At the WeWork Manhattan location, for example, KPMG rents about 75 desks which it splits between workers who provide business services to start-ups, and another team that advises corporate clients on technological innovation.7 Other multiple-location business ventures are being developed by serial entrepreneurs, primarily in the USA and across Europe. Second Home, a members-only workspace based in London, recently announced European expansion plans that will begin with the opening of a Lisbon location in late 2016.8

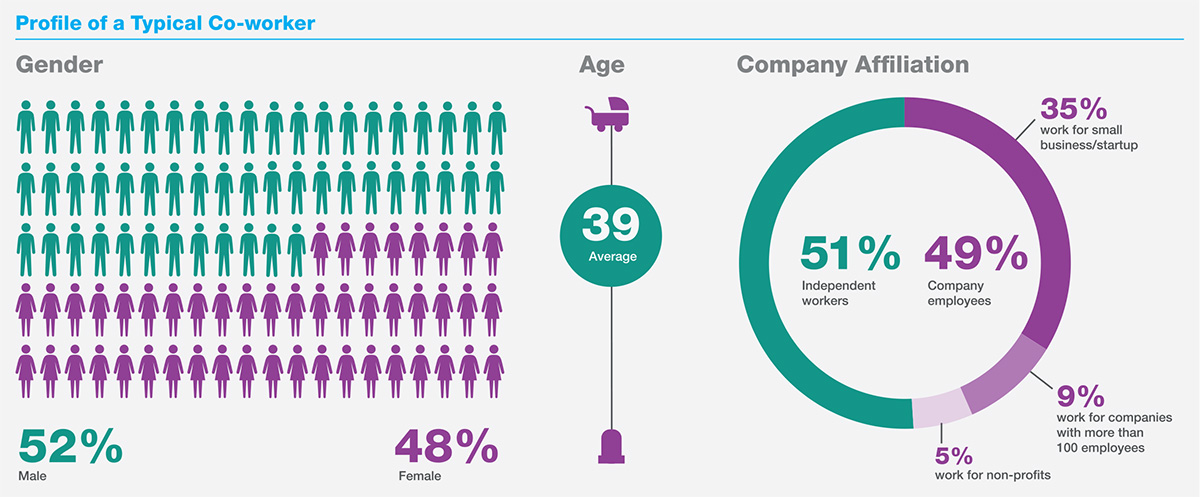

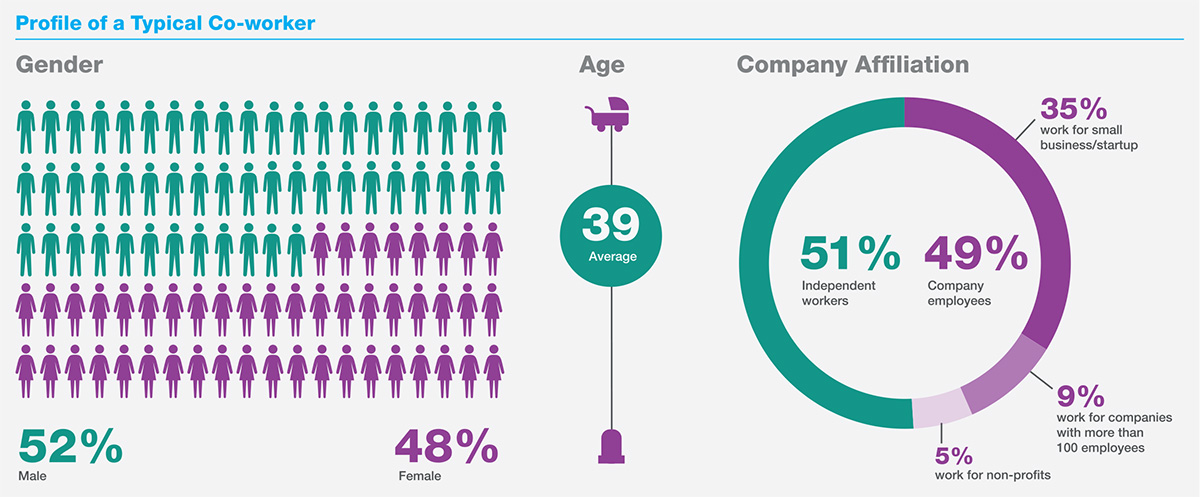

Although current co-working spaces vary in terms of business model, size, specialisation and amenities, most are set up to accommodate individuals or groups that are not typically employed by a single organisation, but share certain values and are interested in the synergies which can occur from working with like-minded people in the same space. According to a 2015 survey conducted by Emergent Research, the average age of co-workers is 39 years old, and 52 per cent are male; only 9 per cent work for companies with more than 100 employees (Figure 3).9

Figure 3. The average age of a co-working space member is 39, as reported by Emergent Research; only 20 per cent of members are younger than 30 and 7 per cent are older than 60.

Why Businesses Embrace Co-working

A broad range of mid and large-sized corporate organisations have chosen co-working strategies as part of their supplementary, and sometimes even primary, office solutions. These strategies typically follow one or more of the following scenarios:

Figure 4. Based on data from Emergent Research in partnership with Intuit Inc., the long-term trend of hiring contingent workers will continue to accelerate in the near future.

-

Placing individual employees in community co-working environments so they can experience the communal benefits reported by independent co-workers. This alternative is most often used for remote or work-from-home employees who are physically disconnected from co-workers.

-

Integrating co-working spaces within the company's office workplace strategy, either by leasing portions of an off-site co-working space to accommodate specific employee teams or by creating a co-working environment on site in an existing corporate-owned or leased office. This strategy is most commonly used for innovation, engineering and R&D teams as well as for HR professionals.

-

Leasing corporate facilities to vendors, sub-consultants, business partners or other non-employees for use as co-working space. This strategy has been embraced by firms with progressive cultures, primarily those in the technology sector.

Coca-Cola was an early adopter of internal co-working, establishing a 70-person space at its Atlanta headquarters in 2013. Created to stimulate innovation and entrepreneurial behaviour, the space is home to a 3-D printer and has hosted a series of start-up weekend events where Coke employees collaborate on new product ideas.

The unique advantage of integrating coworking spaces within an organisation’s existing office environment is that it enables CRE professionals to continually adapt and experiment with office configurations, aesthetics and amenities until they hone in on an environment that is ideally suited to the individuals and teams working in the space. It also helps organisations to better identify the profiles of individuals and teams that are most likely to thrive in these co-working spaces. Worldwide, the ongoing shift towards free-agent employment is contributing to the proliferation of these corporate co-working strategies. As traditional employers continue to hire a growing number of contingent workers — such as freelancers, part-time employees and independent contractors — shared work and environments are a flexible, efficient strategy for accommodating this employment transition (Figure 4). Although business approaches to co-working vary widely, the goals that drive a co-working strategy are primarily focused on several common ideals: to attract and retain talent, drive innovation, build community, optimise productivity and use space more efficiently.

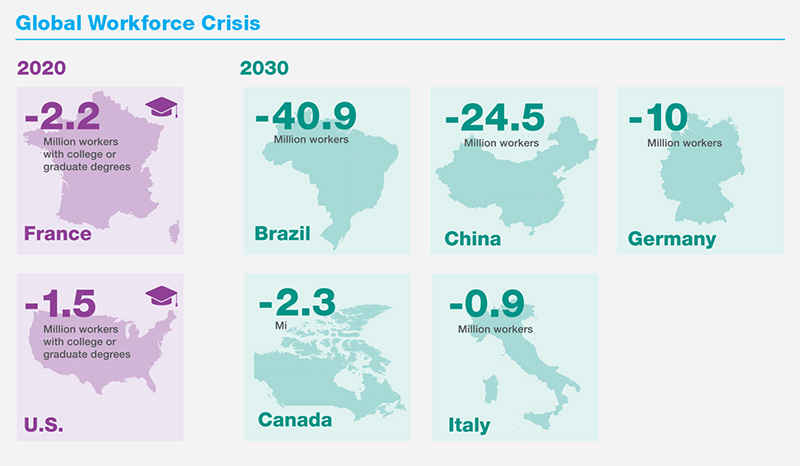

Support attraction and retention

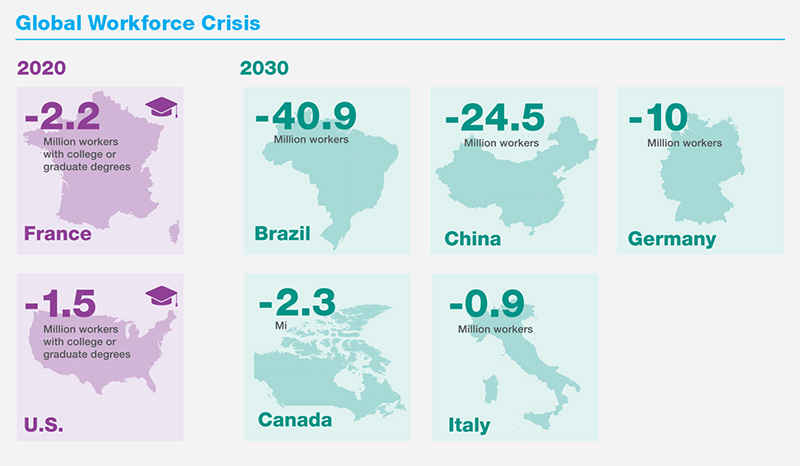

Talent management is foundational for most businesses that choose co-working strategies. Human capital is the vital component that enables organisations to identify creative approaches to innovation, increase speed to market and quickly respond to customer demands. A projected talent shortage adds a sense of urgency to attraction and retention challenges. By 2020, the USA is projected to have 1.5 million too few workers with college or graduate degrees, while, for example, the workforce in France could be deficient by 2.2 million degree holders.10 Simulations of 25 major world economies conducted by Boston Consulting Group revealed crippling labour shortages by 2030. These projections include a shortfall of up to 10 million workers in Germany, 40.9 million in Brazil, 24.5 million in China, 2.3 million in Canada and 0.9 million in Italy (Figure 5).11 What is more, the turnover costs associated with recruitment, training, lowered productivity and lost expertise are significant. The average cost to replace an employee is one-third the annual salary of a new hire, according to US Labor Department estimates.12 Some estimates are even higher: a study by the Society for Human Resources Management (SHRM), for example, revealed that replacing an employee can cost between six to nine months of salary.13

Figure 5. Based on research from both McKinsey Global Institute and Boston Consulting Group, there will be a worldwide shortage of talent in the years ahead.

Figure 6. Only 13 per cent of employees worldwide are engaged at work according to Gallup research. The bulk of employees worldwide — 87 per cent — are ‘not engaged’ or are ‘actively disengaged’.

Figure 7. The most cited ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ of jobs across industries and the globe according to millions of reviews collected by Glassdoor.

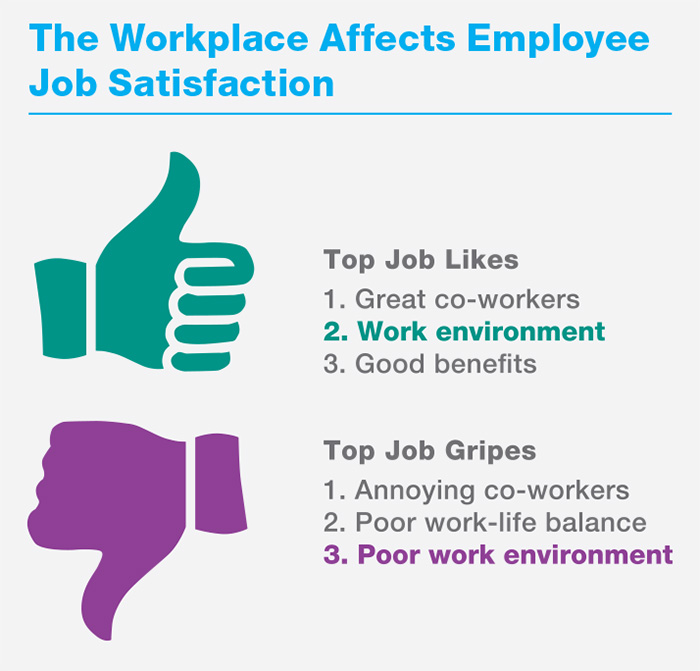

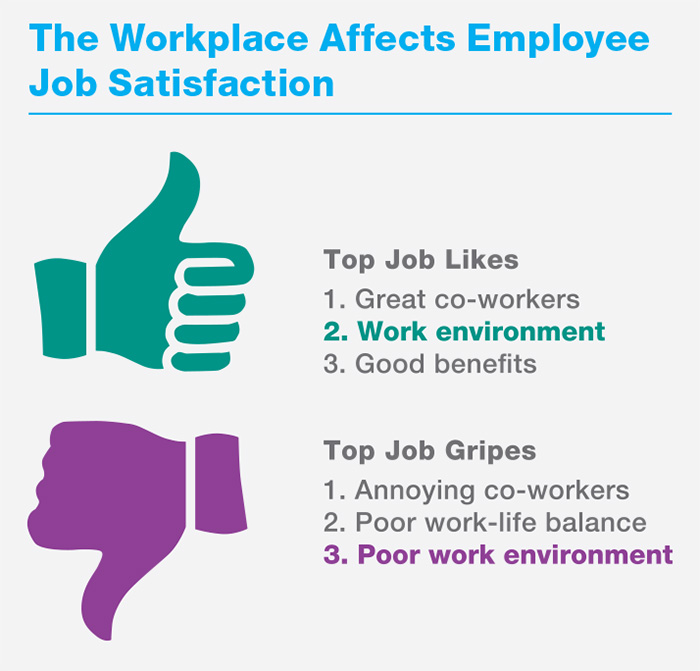

Further complicating these HR challenges, only 13 per cent of employees worldwide are engaged at work, according to a 142-country study of 180 million employees conducted by Gallup in 2013.14 In the survey, 87 per cent of respondents reported that they were either ‘not engaged’, meaning they lacked motivation and were less likely to invest discretionary effort in organisational goals or outcomes, or were ‘actively disengaged’, indicating they were unhappy and unproductive at work and liable to spread negativity to co-workers (Figure 6). This translates to approximately 1.2 billion disengaged workers. Addressing these disengaged and dissatisfied employee populations requires employers to recognise, among other issues, the significant impact of the physical work environment on job satisfaction and an organisation’s overall performance. A broad poll of millions of company reviews across industries and the globe on the job and recruiting site Glassdoor revealed that the work environment was the second biggest job like of employees and a poor work environment was the third biggest job gripe (Figure 7).15 These insights build a compelling case which suggests that the workplace environment must become a strategic imperative in both the war for talent and advancing an organisation’s mission.

Additionally, as businesses seek to attract junior-level employees to their organisations, they are discovering the importance of replicating the environments offered on today’s college campuses, where an estimated onethird of US business incubators are located.16 Influenced by their campus experiences, millennials are entering the workforce with an expectation that they will have access to similar environments where they can collaborate, explore and create. Many technology businesses have responded with the development of distinct spaces, competitions and events to attract and motivate employees at all levels. One example is the Microsoft Garage, a project lab that invites employees to work on projects which may have no relation to their primary function within the company. Located in Bill Gates’ former office on the Microsoft campus, the space is open to employees at any level and from any company division. Similarly, LinkedIn’s [in] cubator programme allows any employee with an idea to organise a team and pitch a project to executive staff once a quarter. Facebook hackathons encourage the company’s engineers to unleash their talents and creativity in all-night coding sessions, one of which spawned the social network’s ubiquitous ‘Like’ button. These examples take the spirit and advantages of co-working and imagine their logical end, creating literal room for unforeseen discoveries and valuable innovations.

Drive innovation

Because co-working spaces are conducive to creativity and idea sharing, they are ideal work environments for innovation, engineering and R&D teams. The dynamic energy and start-up vitality present in co-working spaces support efficient product or process development, enabling businesses to generate and commercialise ideas quicker to gain a competitive advantage in the marketplace. The flexibility and culture of co-working spaces also provide businesses with the opportunity to leverage external R&D expertise without making a capital-intensive investment. By providing organisations with a line of sight to local networks of innovators and entrepreneurs, co-working spaces offer companies valuable opportunities to connect with local talent and broaden their innovation pipeline.

Less formally, businesses can use co-working spaces to host ongoing programmes to generate new ideas. Coca-Cola created its start-up weekend as a way to inspire internal staff to develop innovative ideas. The company also hosts an incubator programme that allows it to invest in and sometimes acquire or license from its business partners. AT&T created the Foundry, a network of research centres within which its engineers work side-by-side with handpicked start-ups, corporate partners and third-party developers to bring new products to market.17

Co-working also allows businesses to expand into new markets with little risk. AstroLabs, an entrepreneurship consulting firm based in the Middle East, partnered with Google to open a co-working space and educational centre in Dubai. The space, which is Google’s first in the Middle East and North Africa region, helps start-ups to scale their ventures and expand globally. Located in the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC) free zone, the tech hub features a Google for Entrepreneurs Device Lab, a quiet area designed for programmers and a coffee area that is open to the public.

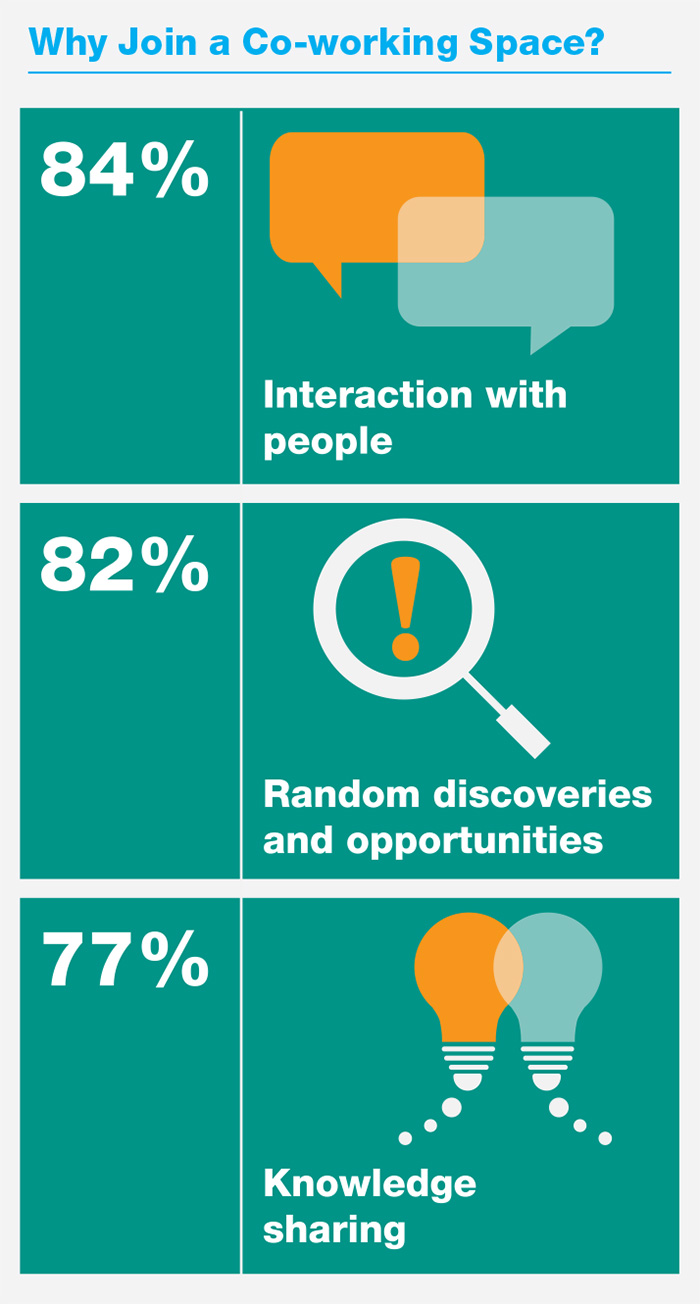

Figure 8. Top drivers for joining a co-working space based on a survey of more than 200 US co-workers by Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan.

Build community

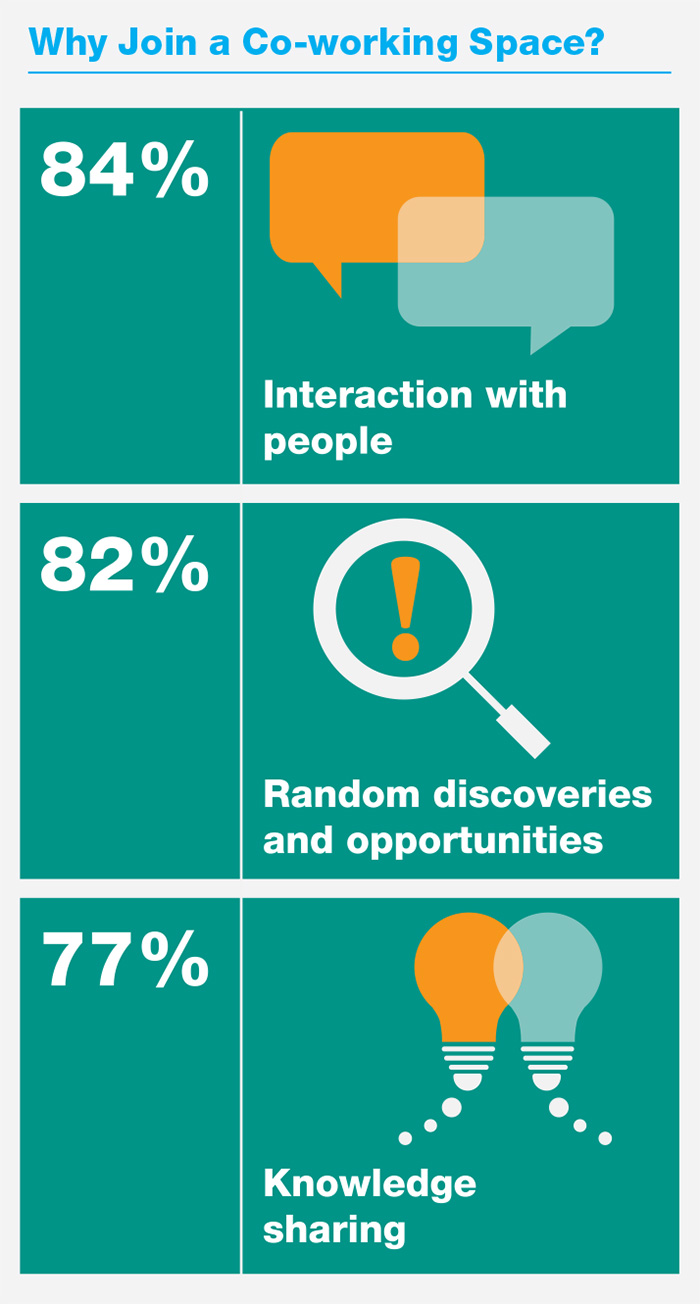

At its core, co-working seeks to create strong communities and foster synergies, adding greater value to everyone who participates in the scheme. The dynamic energy of these spaces helps people to feel like they are part of something larger than themselves and that others care about their success and want to help propel their ideas forward. A 2014 survey of more than 200 US coworkers conducted by researchers at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan confirmed that belonging to a community was the most common reason for people to seek out a co-working space. Eighty-four per cent of respondents cited interaction with people, followed by random discoveries and opportunities (82 per cent) and knowledge sharing (77 per cent) (Figure 8).18 Additionally, a growing body of empirical research supports the link between positive social connections at work and beneficial health and productivity outcomes. In studies conducted by Gallup, it was concluded that close work friendships boost employee satisfaction by 50 per cent, and people with a best friend at work are seven times more likely to engage fully in their work. Although most of today’s office environments promote formal and informal collaboration, they typically lack opportunities for serendipitous idea sharing among a broader community of complementary individuals or businesses. In contrast, co-working spaces can provide people with greater opportunities to meet a wider variety of new people and discover new ideas, identify talent, make deals and host events that target potential customers, partners and collaborators. Akerman, LLP, a top 100 US law firm based in downtown Miami, established a satellite office at The LAB Miami, a business incubator in Miami’s Wynwood Art District, in 2013. According to Chairman and CEO Andrew Smulian, the strategy is part of the firm’s ‘institutional commitment to weave our lawyers — in Miami and across the firm’s national platform — into the fabric of the grassroots entrepreneurial movement’.19

Optimise productivity

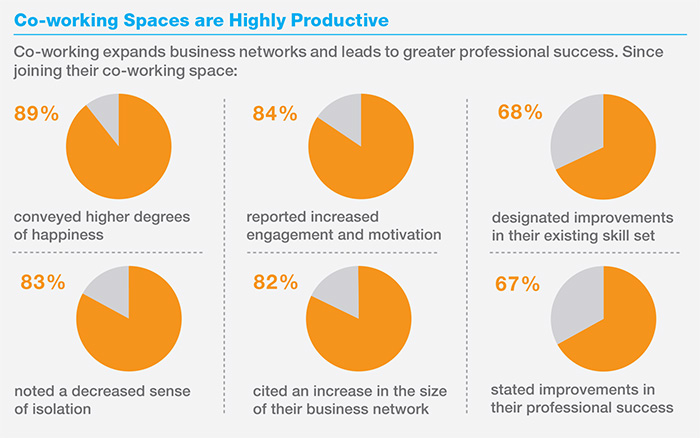

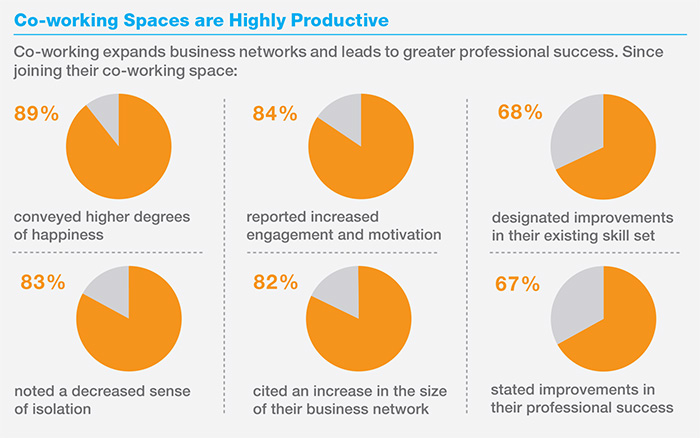

Co-working spaces are highly productive when compared to employees working on their own. Eighty-four per cent of individuals surveyed in a 2015 study of 1,500 co-workers in 52 countries reported they were more engaged and motivated since joining their co-working community, 82 per cent cited an increase in the size of their business network and 83 per cent reported a decrease in their sense of isolation (Figure 9, Page 5).20 People often say they prefer to work in coworking spaces because they believe that their performance will improve more rapidly than in a traditional office environment or at home. They cite factors such as built-in peer accountability, a fast-paced environment and flexible amenities as key elements which contribute to their productivity. Co-working spaces also allow individuals control over their work environments, enabling them to choose how, when and where they work. This inherent flexibility contributes to a ‘judgment-free’ environment where work schedules are expected to be variable, and there is no pressure from others to conform to a consistent 9–5 work pattern. In a post-occupancy study conducted by Knoll of Galvanize 1.0, a technology business incubator and shared workspace in Denver, members reported spending one-third of their time away from their desk and splitting their time equally between focused work and interactions with others.21

Co-working may also allow employees to reduce unproductive time spent in commuting back and forth to distant corporate facilities. Plantronics Inc., which develops audio communications products and solutions for businesses and consumers, allows its employees to choose whether to commute to its headquarters office in Santa Cruz, California, work from home or join one of nine NextSpace co-working locations.

Because of the breadth of people and resources available in co-working spaces, they are effective learning environments. Knowledge-sharing opportunities include traditional workshops and presentations as well as online coursework, peer-to-peer exchanges and mentoring programs.

Figure 9. According to research by the Global Coworking Unconference Conference and Emergent Research, co-working membership increases engagement, motivation and other business objectives.1

Improve space utilisation

Co-working strategies can lower a company’s real estate costs and provide greater flexibility in procuring and managing space. As a business strategy, co-working can be more cost-efficient than creating dedicated office space in certain markets with a large percentage of highly mobile employees. For businesses seeking to quickly enter new geographic markets, co-working also provides a more efficient alternative to planning, designing, constructing and relocating to a new permanent office space. When Amazon initiated a strategic expansion into the Boston market in 2012, for example, the online retailer opted to lease space at CIC Cambridge, a co-working community located in the heart of the city’s technology hub. The space served as a temporary outpost for Amazon until the company could build out a permanent local office location. Even after the build out, CIC Cambridge continued to provide overflow space to Amazon, as necessary, to accommodate the company’s local growth. As the structure of work becomes less fixed to a particular time and place, the traditional CRE model of assigning all employees to particular spaces and assigned desks in a single building is increasingly viewed as an unproductive investment. Because a significant percentage of workspace in a typical corporate office setting is vacant at any given time, co-working represents a logical strategy for improving space utilisation and overall efficiency.

Perceived Drawbacks

Despite the many benefits of co-working, several negative perceptions may deter companies from seriously considering external co-working spaces for their employees. Following are some of the most common concerns.

CASE STUDY 1

Galvanize 1.0 offers choice by creating a space for many purposes

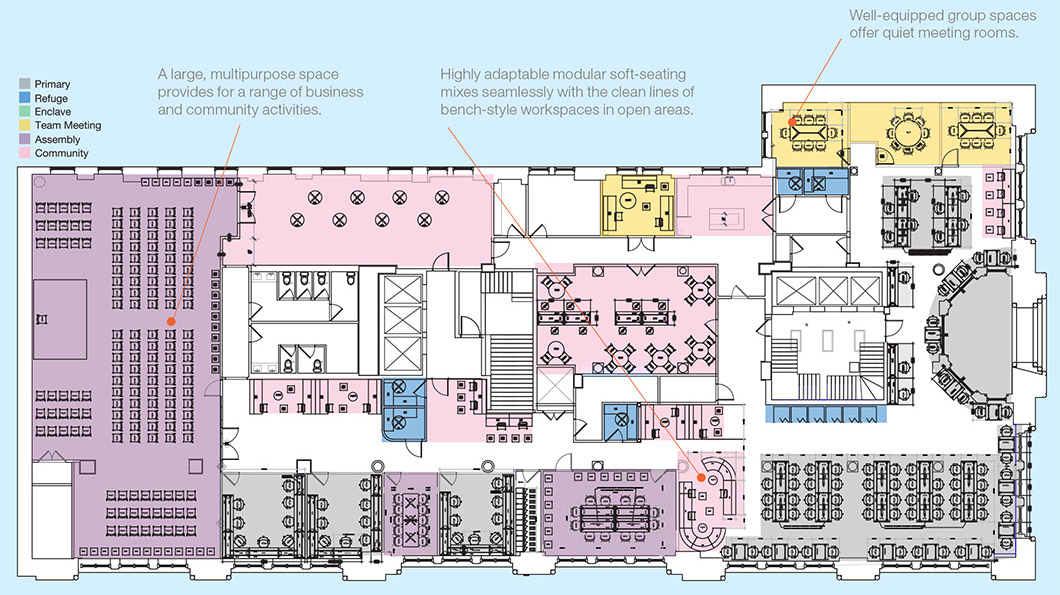

Designed to give entrepreneurs and innovators the best chance for a successful launch of their new ventures, Galvanize created an ‘innovation ecosystem’, which is a space defined by growing start-ups through capital, community and curriculum. Its ecosystem offers support for every phase of the business development process, ranging from shared areas for one or two people to large suites for ten or more (Figure 10). The space is designed to facilitate this collaboration and start-ups are encouraged to work together and draw in ideas from various points of view. The Galvanize motto states: ‘Chance favors the connected mind’ and, as a result, work areas, amenities and collaboration areas — ranging from touch-down ‘hot desk’, a public café with premium coffee to media enclaves with plug-and-play technology — are abundant throughout the space (Figure 11).

Figure 10. A variety of work and collaboration areas are planned throughout the Galvanize ecosystem.

Figure 11. The hub of Galvanize is a café, bar and lounge area, where guests and co-working members are encouraged to convene over food and drink to exchange ideas.

Inconsistent office culture

Because a co-working space is often composed of individuals representing diverse organisations, there may be limited ability to shape or change an office culture to reflect an organisation’s unique values. It also can be more difficult to maintain a common team spirit when employees are working at different locations with distinct atmospheres.

Lack of connection

Due to their co-location and in-person interactions with other co-working members, employees working in an off-site co-working space might actually develop closer relationships with colleagues from other companies rather than building a collaborative bond within their own organisation. In addition, these remote employees may feel a disconnection from day-to-day business operations and might worry about being overlooked for career development opportunities.

Excessive noise and distractions

The acoustical challenges and visual distractions that can interfere with concentration in any open plan space layout may be even more significant in a transitional co-working environment. The wide range of businesses, roles and personalities present in these spaces can contribute to an unpredictable environment that lacks the common courtesies of a traditional office.

Security, intellectual property and other competitive concerns

Although security breaches are possible in any office environment, they carry greater risk in an environment where individuals do not share the same employer and may not even know each other. With the transparency and openness that characterise co-working environments, businesses must be extra diligent at protecting their competitive assets, including intellectual property and confidential or sensitive company information. Most importantly, organisations need to consider their employees; in a highly competitive marketplace, co-working environments can provide an opportune recruitment location for competing organisations.

The Bottom Line

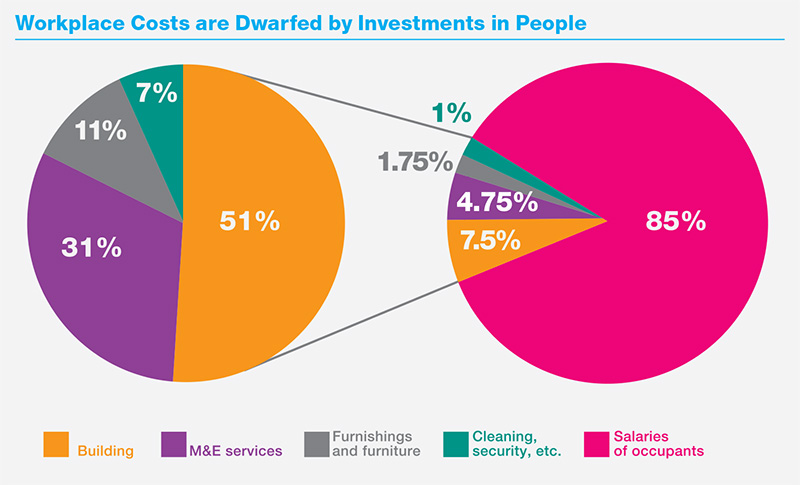

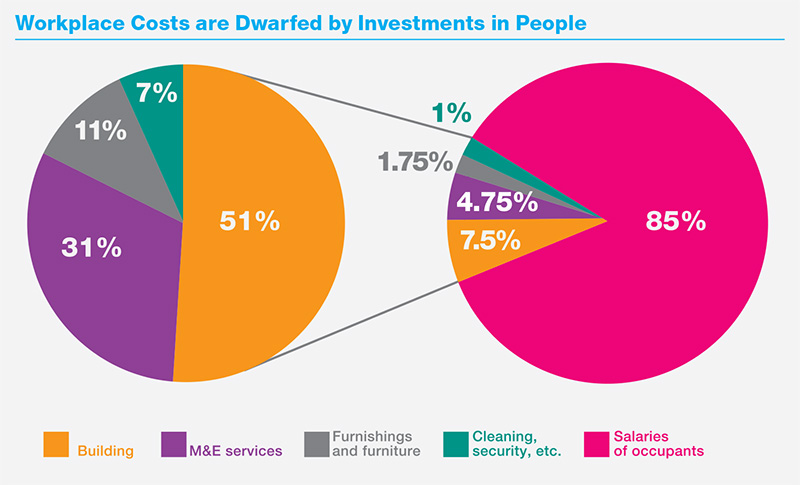

Why should CRE executives pay attention to co-working trends? In short, because people are a company’s greatest investment, and their productivity and satisfaction are key to the organisation’s future performance and overall competitiveness. Construction and maintenance costs represent 51 per cent of the total expenses of developing, owning and operating space in a typical office building, over the 25-year term of an occupational lease. The remaining 49 per cent of costs are devoted to mechanical and electrical (M&E) services, furnishings and other operational expenses.23 But, with salaries and benefits added to the equation, only 7.5 per cent of a company’s total investment covers building construction and maintenance, while 8.5 per cent is devoted to furnishings, M&E services and other operational costs. The balance — 85 per cent — covers the salary and benefits costs of building occupants (Figure 14).24 As a result, factors that influence and improve the effectiveness of staff will have a far greater financial impact than those that only affect space efficiency. CRE and facilities departments which embrace co-working as a practical real estate strategy can contribute to improving an organisation’s overall performance by providing flexible, productive work environments that foster collaboration, innovation, extended networking and passive recruiting. As co-working principles continue to evolve and influence broader ‘co-learning’ and ‘co-living’ concepts, businesses that integrate these progressive strategies into their own enterprises will be well equipped to meet the needs and expectations of the future workforce.

Figure 14. The cost of providing accommodation for office workers in terms of both capital construction costs and building operation costs is diminished by the costs of their salaries and benefits. 23

CASE STUDY 2

The business of serendipity — Civic Hall nurtures connections

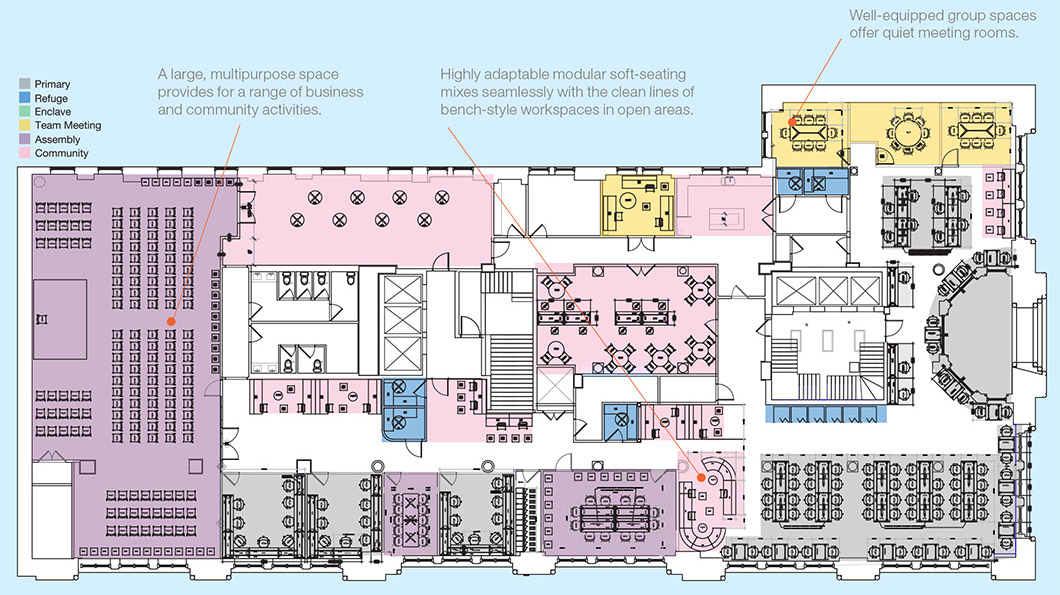

‘We’re in the business of serendipity’, stated Heidi Sieck, Chief Community Officer at Civic Hall, a work-and-community space in New York City (Figure 12).22 The space was established as a way to nurture connections focused on the technology which can improve the civic life of communities. Configured to support a range of activities — ranging from day-to-day working and collaborating to large group gatherings that include lectures, seminars, conferences and receptions — the space needs to be able to flex and adapt (Figure 13). This flexible functionality is fundamental to the design of the space, enabling the community centre to serve and connect a highly diverse population that ranges from business and government to academia, journalism and politics.

Figure 12. Creating serendipitous opportunities for connection and collaboration is a primary goal of Civic Hall and the space is designed and furnished to facilitate such meetings.

Figure 13. Creating serendipitous opportunities for connection and collaboration is a primary goal of Civic Hall and the space is designed and furnished to facilitate such meetings.

Download "The Rise of Co-Working" to Read the Full Paper

References

(1) Global Coworking Unconference Conference/Emergent Research (2015) ‘Fifth global coworking survey’, November, available at: deskmag.com. http://officeslicecoworking. com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/GCUC-2015-Coworking-by-the-Numbers. compressed-1.pdf, Accessed 11 November 2015.

(2) Global Coworking Unconference Conference/Emergent Research (2014) ‘Fourth global coworking survey’, November, available at: deskmag.com. http://www.deskmag.com/en/the-coworking-market-reportforecast-2014, Accessed 11 November 2015.

(3) Building Owners and Managers Association (2015) ‘Office experience exchange report’, online. https://eer.boma.org/Boma/marketing.aspx, Accessed 6 December 2015. [only available to subscribers]

(4) Foertsch, C. and Cagnol, R. (2013) ‘The history of coworking in a timeline’, September, available at: deskmag.com. http://www.deskmag.com/en/the-history-of-coworkingspaces-in-a-timeline, Accessed 11 November 2015.

(5) MBO Partners (2015) ‘State of Independence in America 2015’, p. 5. https://www.mbopartners.com/uploads/files/state-of-independence-reports/MBO-SOIREPORT-FINAL-9-28-2015.pdf, Accessed 17 December 2015.

(6) Kesler, S. (2016) ‘WeWork valuation soars to $16 billion’, Fast Company, March, online. http://www.fastcompany.com/3057670/wework-valuation-soars-to-16-billion, Accessed 7 January 2016.

(7) Clark, P. (2016) ‘Co-working spaces are going corporate’, BloombergBusiness, February, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-19/co-working-spaces-aregoing-corporate, Accessed 7 March 2016.

(8) Butcher, M. (2016) ‘Second Home raises $10.7m from Yuri Milner, Martin Lau, Index and plans Lisbon home’, January, available at: techcrunch.com. http://techcrunch. com/2016/01/18/second-home-raises-10-7mfrom-yuri-milner-martin-lau-index-and-planslisbon-home/, Accessed 23 January 2016.

(9) Global Coworking Unconference Conference/Emergent Research, ref. 1 above

(10) Manyika, J., Lund, S., Auguste, B. and Ramaswamy, S. (2012) ‘Help Wanted: The Future of Work in Advanced Economies’, McKinsey Global Institute, New York, March, p. 5.

(11) Strack, R., Baier, J., Marchingo, M. and Sharda, S. (2014) ‘The global workforce crisis: $10 trillion at risk’, Boston Consulting Group, July, https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/management_two_speed_economy_public_sector_global_workforce_crisis/, Accessed 17 December 2015.

(12) US Labor Department.

(13) Allen, D. (2008) ‘Retaining Talent’, SHRM Foundation, p. 3.

(14) Gallup (2013) ‘State of the Global Workplace’, Gallup, p. 11.

(15) Glassdoor (2014) ‘10 Biggest Job Likes and Gripes of Employees’.

(16) Pappano, L. (2012) ‘Got the next great idea?’, New York Times, July, p. ED10.

(17) Waber, B., Magnolfi, J. and Lindsay, G. (2014) ‘Workspaces that move people’, Harvard Business Review, October online.

(18) Seppälä, E. and Cameron, K. (2015) ‘Proof that positive work cultures are more productive’, Harvard Business Review, December, online.

(19) Smulian, A. (2013) ‘Akerman Senterfitt’s Collaboration with The LAB Miami and the Local Startup Community Showcased in the Media’, Akerman web site.

(20) Global Coworking Unconference Conference/Emergent Research, ref. 1 above.

(21) Knoll. (2013) ‘Galvanize 1.0: In Focus, Knoll Project Case Study,’ Knoll, Inc.

(22) Sieck, H. (2015) ‘Civic Hall, Knoll Project Case Study’, Knoll, Inc.

(23) Commission for Architecture & the Built Environment and British Council for Offices (2005) ‘The Impact of Office Design on Business Performance’, p. 44.

(24) Ibid.

Further Reading

Lapowksy, I. (2012) ‘Why every company is now an incubator’, Inc. Magazine, December, online.

Manpower Group (2015) ‘Talent Shortage Study’

Spreitzer, G., Garrett, L. and Bacevice, P. (2015) ‘Should your company embrace coworking?’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Fall, pp. 27–29.

Trotter, A. (2013) ‘Six lessons for corporations building innovation accelerators’, Innosight Strategy & Innovation newsletter, August, online.

Verhoeve, W. ‘A Look at Co-Working Spaces’, Knoll, Inc.